Legal Talks

Access to Justice: Judiciary During this Pandemic

Fanan Rasheed

Sastra University, Thanjavur, Kerala

The dreadful pandemic named COVID-19 is a major global crisis not only in terms of the toll it has taken on human life, businesses, jobs, falling of economy, restriction in freedom of movement and associations but also due to denial of the basic right to justice promised by the constitution. It has resulted in a revolutionary and historical change in the mode of serving justice by law. The COVID-19 pandemic has redefined ways of living. New methods have been adopted in every field: be it, online classes, for schools and colleges or e-courts for hearing.

In India, after complete lockdown got imposed nationwide on March 26, the Supreme Court decided to discontinue face to face court proceedings and take up only urgent cases that too virtually. There is no physical courtroom or any means of physical contact ensuring safety during covid times. All the lawyers, judge and litigants are to take part in proceedings through video conferencing facilities. The pleadings are filed digitally via e-filing centers. Across the country, since courts now take upon only urgent cases, it has resulted in the low disposal rates. This came as a blow to the otherwise underprivileged, poor, sensitive or somewhat invisible, neglected and inferior sections of the society who now felt outcast as they had mere knowledge on the usage and working of technology. Most advocates and litigants are unaware of and have no prior exposure to the use of such digital mediums.

Let’s look briefly on how e-courts function: in such courts, the case files are digitalized as PDF and then converted into portfolios containing records of the cases. The Judge has been provided with a Wacom 24 or 27 high-resolution monitor with ‘Stylus’ which respond to the slightest touch, which allows the Judge to move across the portfolios of cases and write down personal notes as and then required simultaneously. The lawyers can present their cases through electronic gadgets like laptops, tablets etc., and if need be the lawyers can also display their screens. Advocates are forced to be brief about their presentation as digitalized mediums have specific time constraints. Litigants are given the privilege to attend and be part of court proceedings from the comfort of their homes without otherwise having to travel long distances to come to actual courts.

According to a survey: In Indian courts, there is a fall in case numbers also approximately 3.23 crore cases are pending, which includes 90 lakh civil cases and 2.32 crore criminal cases. Some significant problems associated with this new method of judicial proceedings are: It is accepted worldwide that hearings over video-conferencing are not even close to satisfactory. Connections are not always smooth and are often disrupted with frequent audio and video drops. There is a much higher chance of justice being denied as compared to physical court hearings. The income of advocates have significantly reduced, and a significant fraction of these individuals want the old system to be restored. While higher-level courts have functioned without much of a problem, most district courts have mostly remained closed for routine work. Not all lawyers possess resources like tablets and laptops with web-cameras, microphones and uninterrupted net connections. Many are not even aware of creating and uploading pdf documents.

For litigants, the situation is even worse. Even though an online system has come into play for the judiciary, most courts are close to a shutdown. Individuals in prison are denied bail; trials are at a standstill, petitions are kept pending. The wealthy and better off can afford and appoint influential and high profile lawyers for their cases, whereas ordinary litigants are less fortunate. Prashant Bhushan, the famous supreme court lawyer has argued that all of this has resulted in a lack of addressal of the fundamental rights of citizens like those in detention, the sick and poor.

There have been many instances of the saying- “Justice delayed is justice denied” like the migrant workers were left stranded without jobs, money or food after lockdown. They wished to return to their houses and reunite with their families. These labourers overcrowded train, bus stations and state borders. Police stopped them at state borders and put them in shelter homes upon order of the central government where number of people had to live in confined spaces devoid of social distancing. Also, the quality of the food provided was inferior, with many getting just one meal of uncooked food every day. A Rs 1.70 lakh crore package was given 36 hours after the lockdown, in response to the petitions about the same. The needs of the migrant labourers were not addressed by any of the schemes announced. Since they do not possess certain documents like ration cards, address proof, etc., the public distribution system also excludes such people.

On March 29, 2020, an order was passed by the government that denied the labourers a safe return to their respective villages. Further, employers were told to pay wages to their workers and landlords were asked not to charge rent.This led to a belief that even though the suffering of poor is a constitutional concern, the Supreme Court is not be looked upon for answers.

With this as a primary concern, social activists Harsh Mander and Anjali Bharadwaj, who had been working hard to look after these workers at various places in Delhi filed a petition seeking an arrangement of minimum wages for these people. On April 3, 2020, during the preliminary hearing, the Union of India was asked to respond to the allegations. The matter was then postponed to April 7, 2020. The petition, though aimed at providing relief to migrant workers, was turned by the court into seeking orders to limit the media from reporting about the spread of the coronavirus. The court further adjourned the case to April 20, 2020. The court failed to sit nor state any reason for not doing so on April 20, 2020. The only thing that the petitioners wanted enforcement of Article 21 – the right to life– of workers who had been deprived of their wages and livelihood by the lockdown imposed. However, all these efforts were in vain as the supreme court gave in its power of review of the government’s policies and actions. The same was the condition for Mahua Moitra and Swami Agnivesh who gave petitions on behalf of migrant labourers.

During the lockdown, the police were strictly advised to be indulged in imposing the lockdown; the Delhi Police was instructed to continue arresting people related to the communal riots that happened in February. Muslims, despite being the primary victims of the violence and having to escape their homes were unsympathetically arrested in huge numbers, especially youth who peacefully protested about the CAA or NRC. The Criminal Procedure Code was violated according to which the names of those who were arrested had to be disclosed by the police. It indeed was impossible for anyone to access information on people who got arrested during the lockdown. Judiciary should treat this lockdown as a chance to showcase courts as a service rather than a mere place. There must be plans to conduct actual hearings or running courts in shifts. Just in case any court needs to conduct physical court hearings, they need to implement some guidelines such as only those lawyers/litigants whose cases are there for the day’s hearing should have permission to enter court halls. Thermal image cameras must be set up at the doorway of court building, to spot affected or potential individuals. There should be specialized individuals assigned for checking the papers and other objects carried by the lawyers/litigants without having to touch the same. At the doorway, there should be a hand wash kept to make sure sanitization of each and everyone who enters and exits the court premises. There should be strict rules and regulations on the working of public services like canteens within the court with all precautions. Masks, gloves and sanitizers should be provided. Citizens or rather the laymen hope that open court hearings would be reinstated within the near future as soon as possible. Access to justice is a fundamental right of a person that no pandemic, person or institution can seize them from!

Legal Talks

Biting the Cookie: Informed Consent and The Right to Privacy

Mahathi U

The National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi, Kerala

The methods of production, collection, combination, sharing, storage, and analysis of data on the internet are rapidly reorienting and thereby redefining personal data and the protection that ought to be given to it. Owing to this constant change, online privacy remains a predicament to consumers, policymakers, and web organizations.

When a website reads, “We use cookies to give you the best online experience,” this message is either ignored or accepted by the user. In doing so, little does the user know about these tiny text files that can be used to intrude into his privacy and access his data. Neither the Data Protection Bill nor the IT Act contains provisions to regulate cookies. A few provisions are so broad that cookies might fall under their ambit. But such legislative gaps only serve to weaken the privacy of people using the internet. This article attempts to propose a stipulation in Indian law to monitor and control the use of cookies on the world wide web.

That’s How the Cookie Crumbles:

The archetypal method of locating and tracking user activity online entails placing small text files or “cookies” on a user’s hard drive, which are given back to that website during successive visits by the user. They may be designed to stay on the hard drive for only the online session, which is currently in progress; they can be fashioned to last for any period or be designed to last eternally.

Undeniably, a few websites need cookies to operate effectively. E-commerce hubs form a part of this category, requiring the placement of cookies in the shopper’s drive in order to discern that shopper as the person who stored his items in his virtual shopping cart (Chapman and Dhillon 2002). However, cookies can make up an invasion of privacy from various standpoints: viz, their capacity to track users’ online behaviour; their clandestineness; their pervasiveness and duration; users’ lack of knowledge regarding the degree of threat they pose, their control and usage and their use by third parties.

The rise in software potentiality that augments user knowledge of efforts to place cookies indicates that greater consilience between disclosure and practice could be favourable to website organisations. Though a priori disclosure of cookies’ usage might lessen the negative effects of cookie detection of the user’s behavioural intentions, concerns about the ‘current process of disclosure’ are extant.

The rampancy of non – consensual identification has increased with the use of third-party cookies and original domain. These issues remain unaddressed and under-regulated by the Indian system.

So, the Indian regime must learn from the EU’s ‘Cookie law’. The EU’s cookie law is essentially a cookie consent directive that protects personal data privacy in the EU. This directive was intended to be the user’s defense against data profiling, tracking user behaviour, the harvesting of personal data without consent, and unwelcome marketing tactics through unsolicited advertisements and other notices.

As per a New York Times report, Europe is now the leading tech watchdog in the world, which is undoubtedly due to the existing cookie law and the broader GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the new ePrivacy Regulation will also strengthen it.

The pop-up windows and cookie consent notices that the user encounters as he surfs the web are attestations to the fundamental right to privacy under European law. Nevertheless, there are flaws in this regime, too, from which the Indian system needs to learn and improvise.

The ePrivacy directive clearly states that trackers and cookies must not be placed before getting the user’s consent, regardless of whether they contain personal data or not, except for those cookies which are strictly necessary for the basic functioning of that website. Despite this, many of the notices and pop-ups merely state that their website “uses cookies to enhance the user experience,” leaving the users with the only option to double-click on the “OK”, to signify their permission to access their personal data.

This results in a condition which is known as ‘consent fatigue.’ The user, in this situation, has no real choice of consent whenever he visits a website. Due to the lacuna, that user’s data continues to be harvested and marketed in the space below the internet visible to the naked eye, which makes up the most of that trillion-dollar economy.

The Indian regime, by not regulating the use of cookies or equivalently efficacious technology, directly enfeebles the right to privacy granted to every person; and every user of the internet, in the instant case. Under the IT Act, Section 43 restricts the access, download, copy, or extraction of any data, computer database, or information from any computer, computer system, or computer network without the owner’s permission or the person in charge. Though this provision may, at large, be taken to include the regulation of cookies, the users’ right to be notified of the presence of cookies in a particular webspace and his right to ‘do-not-track me’ options have not been included.

Privacy as a fundamental right is entrenched in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Data Protection Bill, recommended by the B. N. Srikrishna Committee, does not incorporate this imperative provision to protect said right either. However, it does contain provisions for informed consent with an exhaustive list of requirements to be fulfilled for the consent to be considered informed.

The suggestion made would be to append a provision which protects the personal data of the user, encompassing the facets of informed consent, the due process to be followed to obtain consent, and the rights and duties of a reasonable and responsible user of the internet, assuring the protection of his personal data.

The cookies lurking in users’ hard drive are nibbling away at their privacy and continue to leave a bad after-taste in the mouths of some, so dismiss the role of cookies at your own peril.

The methods of production, collection, combination, sharing, storage, and analysis of data on the internet are rapidly reorienting and thereby redefining personal data and the protection that ought to be given to it. Owing to this constant change, online privacy remains a predicament to consumers, policymakers, and web organizations.

When a website reads, “We use cookies to give you the best online experience,” this message is either ignored or accepted by the user. In doing so, little does the user know about these tiny text files that can be used to intrude into his privacy and access his data. Neither the Data Protection Bill nor the IT Act contains provisions to regulate cookies. A few provisions are so broad that cookies might fall under their ambit. But such legislative gaps only serve to weaken the privacy of people using the internet. This article attempts to propose a stipulation in Indian law to monitor and control the use of cookies on the world wide web.

That’s How the Cookie Crumbles:

The archetypal method of locating and tracking user activity online entails placing small text files or “cookies” on a user’s hard drive, which are given back to that website during successive visits by the user. They may be designed to stay on the hard drive for only the online session, which is currently in progress; they can be fashioned to last for any period or be designed to last eternally.

Undeniably, a few websites need cookies to operate effectively. E-commerce hubs form a part of this category, requiring the placement of cookies in the shopper’s drive in order to discern that shopper as the person who stored his items in his virtual shopping cart (Chapman and Dhillon 2002). However, cookies can make up an invasion of privacy from various standpoints: viz, their capacity to track users’ online behaviour; their clandestineness; their pervasiveness and duration; users’ lack of knowledge regarding the degree of threat they pose, their control and usage and their use by third parties.

The rise in software potentiality that augments user knowledge of efforts to place cookies indicates that greater consilience between disclosure and practice could be favourable to website organisations. Though a priori disclosure of cookies’ usage might lessen the negative effects of cookie detection of the user’s behavioural intentions, concerns about the ‘current process of disclosure’ are extant.

The rampancy of non – consensual identification has increased with the use of third-party cookies and original domain. These issues remain unaddressed and under-regulated by the Indian system.

So, the Indian regime must learn from the EU’s ‘Cookie law’. The EU’s cookie law is essentially a cookie consent directive that protects personal data privacy in the EU. This directive was intended to be the user’s defense against data profiling, tracking user behaviour, the harvesting of personal data without consent, and unwelcome marketing tactics through unsolicited advertisements and other notices.

As per a New York Times report, Europe is now the leading tech watchdog in the world, which is undoubtedly due to the existing cookie law and the broader GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the new ePrivacy Regulation will also strengthen it.

The pop-up windows and cookie consent notices that the user encounters as he surfs the web are attestations to the fundamental right to privacy under European law. Nevertheless, there are flaws in this regime, too, from which the Indian system needs to learn and improvise.

The ePrivacy directive clearly states that trackers and cookies must not be placed before getting the user’s consent, regardless of whether they contain personal data or not, except for those cookies which are strictly necessary for the basic functioning of that website. Despite this, many of the notices and pop-ups merely state that their website “uses cookies to enhance the user experience,” leaving the users with the only option to double-click on the “OK”, to signify their permission to access their personal data.

This results in a condition which is known as ‘consent fatigue.’ The user, in this situation, has no real choice of consent whenever he visits a website. Due to the lacuna, that user’s data continues to be harvested and marketed in the space below the internet visible to the naked eye, which makes up the most of that trillion-dollar economy.

The Indian regime, by not regulating the use of cookies or equivalently efficacious technology, directly enfeebles the right to privacy granted to every person; and every user of the internet, in the instant case. Under the IT Act, Section 43 restricts the access, download, copy, or extraction of any data, computer database, or information from any computer, computer system, or computer network without the owner’s permission or the person in charge. Though this provision may, at large, be taken to include the regulation of cookies, the users’ right to be notified of the presence of cookies in a particular webspace and his right to ‘do-not-track me’ options have not been included.

Privacy as a fundamental right is entrenched in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Data Protection Bill, recommended by the B. N. Srikrishna Committee, does not incorporate this imperative provision to protect said right either. However, it does contain provisions for informed consent with an exhaustive list of requirements to be fulfilled for the consent to be considered informed.

The suggestion made would be to append a provision which protects the personal data of the user, encompassing the facets of informed consent, the due process to be followed to obtain consent, and the rights and duties of a reasonable and responsible user of the internet, assuring the protection of his personal data.

The cookies lurking in users’ hard drive are nibbling away at their privacy and continue to leave a bad after-taste in the mouths of some, so dismiss the role of cookies at your own peril.

Legal Talks

CUSTODIAL RAPE IN LIGHT OF THE MATHURA GANG RAPE CASE

By Nishtha Kheria and Varun Vikas Srivastav

Amity Law School, Noida

Abstract:

In this article, we would like to look at the changes, which came after the monstrous incident took place, i.e. Mathura rape. In the past years, there have been many attempts to bring changes in the laws relating to rape, but the question remains the same has there been any change in the law? If we look at the Supreme Court’s judgments, it is evident that the same ideology is still used as it was in the Mathura rape case. The concepts related to the consent and the non-consent are still the vital issue because even the law changes have not able to address the passive consent. This article will cover why even the modifications bought in law has not been able to bring the changes in the rates of conviction. This is related to law and regards the cases that are not related to rape and is significantly based on sympathy and intentions. By the end of the article, it would be clear that the law is changing every day, but there is a need to mold it so that women’s development takes place as a subject to the law and not as an object.

Keywords: Changes, Judgments, Conviction, Consent, Sympathy.

Introduction

The whole women group had come together as one was when the Mathura rape case took place[i], on 26th of March 1972, the Mathura rape case which was related to the Custodial rape had taken place where two policemen raped a girl who belonged to the Harijan Community in the police station of Chandrapur district of Maharashtra after which the amendment named as the Criminal Law Amendment of 1983 had taken place in the rape laws.[ii]

Facts

In this case, a girl whose name was Mathura who used to work as a labourer in the house for employment. While she was working there, she had developed sexual relations with the son of the place she worked with whose name was Ashok. After which Ashok and Mathura decided to get married. Mathura’s brother had filed an FIR in the police station stating that Ashok had kidnapped her on 26th March 1972. After which, the police took Ashok and Mathura’s statements and asked all other constables to leave[iii].

After the incident had taken place, Mathura was correctly examined by the doctors, and it was said that there was no injury on her body. There were no pubic hair, or semen found instead strays of semen were found on her clothes. The estimated age of Mathura was around 14 to 16 years. [iv]

Issues

The various issues in this case were:

- Had Mathura consented for sexual intercourse?

- Will the accused get charged with section 376 of the Indian penal code?

- Will the acts of the police officers be addressed as rape?

- The decision of the court of acquitting the accused validly?

Arguments

This case argued that the session court had said that the intercourse had taken place with consent because she wanted to fulfil her sexual desires. After which the high court had reversed the trial court’s decision and had held that the sexual intercourse has not consented and was rape. Later, as per the shreds of evidence presented to the supreme court, it was said that Mathura was habitual of sexual intercourse. Both the accused were acquitted and were not charged with Section 376 of the Indian penal code.

The Analysis of Section 376 of IPC

In cases which are provided in Sub-Section (2) then they will be punished with an imprisonment of a term which is not less than seven years or which can extend to ten years and will even have to pay fine until he has not raped his wife or is under the age of twelve years then he will be punished for about imprisonment of two years or with fine or both if the court has a specific reason then they can be imprisoned for less than seven years.

The analysis before the amendment of criminal law 2013

Rape laws have changed a lot of time before attaining the present condition of the criminal law amendment 2013. This amendment took place after the rape case of a physiotherapist in Delhi. Nirbhaya case shook the nation – March 2014. Judiciary spurred into action and laws were strengthened for sex offenders. Four out of the five accused in the horrific gang-rape case of Nirbhaya were convicted and given the death sentence.

The case also resulted in the introduction of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 which provides for the amendment of the definition of rape under the Indian Penal Code, 1860; Code of Criminal Procedures, 1973; the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012.

Rape is defined under Section 375 of the Indian penal code. Rape refers to the act where sexual intercourse takes place with a woman without taking permission and doing through force or fear. Due to Tukaram vs state of Maharashtra (Mathura rape case) the amendment of 1983 was brought.

Due to this case, the amendments had taken place in the evidence act and the Indian penal code. In the Indian penal code, section 376 A to D was added, and in evidence act section 114A was added. Before the amendment of 2013 took place, rape was referred to as the non-consensual sexual intercourse between man and woman. [v]

Rape law after the amendment of criminal law 2013

The amendment of the criminal law 2013 has even provided an amendment in the Indian penal code, evidence act, and the code of criminal procedure related to the laws of sexual offences.

Due to the cases, there was a widespread protest in society because the lawmakers were forced to amend the rape laws. The sole purpose of the amendment was to make the punishments of rape stricter and not to broaden the definition of rape.

Due to the new amendment now the definition of rape includes the punishment for all the kinds of penetration in any part of a girl’s body. This even includes that according to the fifth law commission report, any penetration would consent would be referred to as rape. [vi]

In 2018 a Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance was introduced, which amended the Indian Penal Code 1860. The punishment provided for the rape of women was increased from seven years to ten years.

If rape or gang rape occurs on girls below the age of 12, the perpetrators will suffer a punishment of minimum imprisonment of twenty years and can even get extended up to life imprisonment or the death penalty.

Rape or Gang rape of girls below 16 years of age will also suffer imprisonment of twenty years or life imprisonment. This new ordinance had increased the punishment for girls, but the punishment for rape of boys has still experienced no change.

The Key features of this ordinance are that it amends

Under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860,

- Acid Attack(Sections326A and 326B)

- Rape (Section375, 376, 376A, 376B, 376C, 376D and 376E)

- Attempt to commit rape (Section 376/511)

- Kidnapping and abduction for different purposes (Sections 363–373)

- Murder, Dowry death, Abetment of Suicide, etc. (Sections 302, 304B and 306)

- Cruelty by husband or his relatives (Section 498A)

- Outraging the modesty of women (Section 354)

- Sexual harassment (Section 354A)

- Assault on women with intent to disrobe a woman (Section 354B)

- Voyeurism (Section 354C)

- Stalking (Section 354D)

- Importation of girls up to 21 years of age (Section 366B)

- Word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman (Section 509).

Special provisions to protect women and their interests-

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

- The Dowry (Prohibition) Act, 1961

- The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

- The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986

- The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013.

POCSO Act, 2012, and other laws related to the rape of women. The POCSO, Act states that the higher punishment between the POCSO Act and the IPC will apply to minors’ rape.

Reasons for enactment

The criminal law amendment bill 2013 was formed because of the brutal gang rape and the death of the physiotherapist in Delhi led to the amendment of the laws related to sexual offences in the country. This new act has mainly amended the Indian penal code, code of criminal procedure, and Indian evidence act.

In a case in 2016, there was a case pertains to an allegation of rape by a woman in Bangalore 19 years ago. While the Sessions Court had acquitted the three men accused, the Karnataka high court later sentenced them to life imprisonment. The Supreme Court has set aside the high court judgment and set free the accused, citing reasons including inconsistencies in the woman’s statements, hostile witnesses, and the medical report conducted after the incident.

Judgment was given by the session court

The session court had said that the girl was habitual of sexual intercourse and the intercourse between the accused and the girl was done by consent; therefore, both the accused are not liable for the offense.

Judgment was given by the high court

The judgment given by the session court was then reversed by the high court of Bombay stating that the sexual intercourse taken place was not by consent instead, it was rape. It was proved by evidence that the accused were unknown to Mathura then how can she have sexual intercourse with them through consent.

Judgment by the supreme court

The supreme court had again reversed the order of the high court and said that the sexual intercourse was a consented one and not rape thus agreeing with the session court decision.

Loopholes in the judgment

In the case of Mathura rape case, the various loopholes which should have been taken into consideration were:

- The acquittal was granted to the accused by the supreme court on the sole ground that the girl did not have any injuries; therefore it is not rape.

- It is not a valid reason that there was no alarm for help by the girl then it was consensual intercourse between the police and the girl.

- The greatest loophole was that the accused should have been provided harsher punishments as related to the criminal law amendment.

- The judiciary system should take proper steps in the case of the minors and the majors in such offenses.

Organizations in India helping women in cases of Molestation, Sexual Abuse, and Violence

In 2020 there are various organizations formed for the assisting of women and children during their distress and victims of the Molestation, Sexual Abuse, and Violence.

Some of these organizations and NGOs are

- National Commission for Women Guria India

- Women Helpline (All India)- Women in India

- The Pranjya Trust

- Action Aid India

- Snehalaya

- Majlis

- Azad Foundation

- International Center for Research on Women

- Aasra

- SNEHA

Conclusion

In the case of the Mathura gang rape case, the victims were acquitted by the appellate courts. If we compare both the legislations of both before 2013 and after 2013 then there is a drastic change in the laws related to rape. The Mathura rape case was a case that had received a lot of criticism after the independence and because of which the amendment took place in the criminal law. Then finally after the Delhi gang-rape case in 2013, the laws related to rape have not only changed but the definition of rape has changed and has widened its scope.

[i]B. Suguna (1 January 2009). Women S Movements. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-81-8356-425-0. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

[ii]Basu, Moni (8 November 2013). “The Girl Whose Rape Changed A Country”. CNN. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

[iii]Maya Majumdar (1 January 2005). Encyclopaedia of Gender Equality Through Women Empowerment. Sarup & Sons. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-81-7625-548-6. Retrieved 9 June 2013

[iv]Kamini Jaiswal (12 October 2008). “Mathura rape case”. The Sunday Indian. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

[v]”Rape law, a double-edged sword in India”. CNN-IBN. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

[vi]Sarah Gamble (ed.) (2001). The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Post feminism. Routledge. ISBN 0415243106.

Legal Talks

Tread Lightly: Single Colour and Trademarks

Mahathi U

The National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi, Kerala

That brand behemoths have systematically swallowed up every square footage of high streets is hardly news. Exuberant hues are used judiciously by these brands to draw the consumer towards the product. When such a product sells, fashion brands seek protection from the law for many aspects of clothing and accessory designs, including colours, which can serve as source-identifiers or marks and Trademark law is generally the primary protection sought by fashion brands and designers alike.

This article, for the most part analyses the existing jurisprudence on the single colour mark and the rest emphasizes the need for Indian law to recognize a single colour as a mark, with specific reference to the Louboutin cases.

Fetching sky-high prices and featuring sky-high heels, Louboutin’s red-soled stilettos, are considered to be an utterly iconic symbol of femininity. These fiery red outsoles, have been the subject of many litigations. The first one is Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America[1], with Louboutin suing for trademark protection of his red lacquered sole. In India, the case for red soles[2] has shaken up the judiciary. The High Court of Delhi appears to have slid into a quagmire of sorts because of the three Louboutin cases[3], and the status of the single colour trademark remains uncertain.

Single Colour Mark Jurisprudence:

Drawing a connection between a colour and a brand story, requires more than just ink, pixels, and a lawyer. In Cadbury’s case, the value of owning the colour ‘purple’ would be attached only when it symbolizes a broader brand experience that can delight consumers everywhere.[4] Tiffany’s on the other hand, has been using the sought-after ‘robin blue’ since 1845, but trademarked it only in 1998, all the while managing to retain its brand equity.[5] Both these establishments, in an effort to exclude other brands from deriving any benefit accrued from their unique mark, have sought protection from trademark law.

Under U.S. Trademark Law, the protection awarded to single colours does not extend to colours per se, implying that protection is afforded only to the coloration of a specific product, shape or design.[6] The Pantone Matching System is utilised by the American Judiciary in order to define the scope of trademark protection of a colour so that there exists a standard, objective benchmark that ought to be complied with.[7] The logic behind the confines is that if a colour yields a utilitarian advantage, protecting it as a trademark would unjustly restrict competitors’ ability to compete in the industry.[8]

Contrarily, the Trademarks Act[9] in India does not expressly provide for the protection of single colour trademarks. But the practice guidelines[10] that are drafted by the Trade Mark Office suggest that single colours will be protected on strict evidence of “acquired distinctiveness” and that registration of a single colour will be allowed only to the extent of the colour shade.

This issue had also come up for consideration at the European Court of Justice, which disregarded the recommendation of the Advocate-General and declared the accepted position under European Trademark Law. The provisions of TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) were analysed and applied to the case at hand.[11] It stated that seeking to protect the application of a colour to a specific part of the shoe was admissible. [12]

The single colour mark regime has, ergo, been subjected to interpretation by various legal systems and their views remain divided.

The Rule of Aesthetic Functionality and the Flawed Colour Depletion Theory:

The Court of Appeal in Christian Louboutin SA v. Yves Saint Laurent America[13], addressed the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” as considered by the District Court[14]. The Hon’ble Court also decided on whether the single colour mark was necessarily ‘functional’.[15] The “functionality” of a mark is demonstrated by, inter alia, showing that the mark has a traditional or aesthetic functionality.[16] The common denominator in cases where the functionality doctrine is applied, is whether the element in question has helped in the commercial success of the product.

In order to justify the employment of this rule, the District Court stated that “there is something unique about the fashion world that militates against extending trademark protection to a single colour.”[17] It was in this landscape that the suit was decided against Louboutin. This rationale, however, is faulty for the following reasons.

Firstly, the argument is very general, vague, and the phrase ‘something unique’ has not been elaborated upon. Secondly, the defense of functionality does not guarantee an inordinate range for a competitor’s creative outlet, but only the wherewithal to fairly compete within a given market. Competition considerations must not in any manner outweigh intellectual property rights; they must only step in when necessary.

The Court of Appeal clarified its stance on this issue, denouncing the decision of the District Court. It held that “the District Court’s conclusion that a single colour can never serve as a trademark in the fashion industry was based on an incorrect understanding of the doctrine of ‘aesthetic functionality’ and was therefore error”.[18]

The High Court of Delhi too, in the 2nd Louboutin case[19], seems to have erred in its interpretation of this rule. It has cited the U.S. Court of Appeal as having “categorically observed that where a trademark serves a significant function or the trademark is such that there is a competitive need for the colours to remain available in the industry”, then there remains special reasons which oppose the use of colour alone as a trademark.[20] It has clearly backed the wrong horse by attaching functionality to colour in the case at hand.

The competition versus trademark protection problem in the market is further convoluted by the argument of limited availability of colours, or as it is referred to in the United States, the colour depletion theory.[21]

This theory forms the basis for the Hon’ble Court’s ground for dismissing Louboutin’s plea[22] to recognize his red-sole as a mark, is one that bars the use of colour as a trademark. Its premise which is quite flawed, is that the number of colours in the visible spectrum is finite and therefore, limited. It suggests that if a manufacturer is allowed to appropriate a colour for its goods, and in doing so, is followed by others, at a later point in time, manufacturers will have little to no colours for future utilization.

In the Owens-Corning case, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that, based on a broad revision of trademark law, “courts have declined to perpetuate the colour depletion theory’s prohibition” on infringement protection. [23] This theory has to be rejected because it relies on an infrequent problem in order to legitimize a blanket prohibition.

The Trademark Act, 1999 only allows for a combination of colours to be agnized as a mark under Section 2 (zb)[24]. The object of this provision is to enable the Indian system to prevent the exhaustion of colours. But, in not appending a ‘single colour’ to the section which defines mark, the legislature is denying the right that every brand has, to protect its distinctive identity. This theory effectively denies protection of a colour even after it has achieved secondary meaning resulting in the mischaracterization of the mark as being of monopolising nature.[25]

As amply substantiated above, the rule of aesthetic functionality and the colour depletion theory stand inapplicable in this case, as is.

The Indian Position: What is to be done?

The single colour trademark, forms a grey area in Indian Trademark Law. It purportedly lacks distinctiveness which a combination of colours has. Such an argument is liable to be qualified as unsound and fallacious for reasons which are explained in the following paragraphs.

The latest judgment[26] in the Delhi High Court was decided in Louboutin’s favour. Nevertheless, the judiciary’s only reasoning was that this trademark is protected everywhere and that it has the requisite distinctiveness.

The distorted rationalization in the analysis of the regime is this. Both the Legislature and the Judiciary have developed a misconstrued notion that there might befall a situation where trademarks are to be awarded to colours per se but that is never the case and never will be. The per se rule would essentially deny trademark protection to any application of a single colour on an apparel. Even if the Judiciary wanted to read the per se rule of functionality into this issue, such a rule would be neither appropriate nor necessary here, because this single colour which has been the object of continuous deliberation, will inevitably have to be deployed on a particular product, or serve as an identifier for a specific shape or design. So, undeniably, it cannot be a trademark by and of itself. The secondary meaning or the plus factor is already inherent in the case of a single colour.

Moreover, competition in this billion-dollar industry is not possible without the protection of intellectual property in general and the single colour mark in the instant case. A definitive and acceptable system of protection inspires traders to flesh out new brands and play an active role in business development, thereby helping to maintain a fair competitive market.

The legislation therefore, has to be revamped in such a manner that the definition for mark is inclusive of a single colour. For fear of exhaustion of single colours from the ostensibly limited palette, the judiciary may be satiated by utilising the ‘functionality’ doctrine in the appropriate circumstances, thereby successfully aiding the legislature in preventing unfair competition in the free market.

By extending trademark protection to the coloration of an item of apparel, there is a justified competitive advantage given to a trader. This in turn will serve as a brand-identifier and, brand identity, is a proven neurological mnemonic that influences our thought process. So, dismiss the role of a single colour at your peril.

[1] Christian Louboutin S.A. v Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[2] Specifically, the registration for the Louboutin mark states: “The colour red is claimed as a feature of the mark. The mark consists of a lacquered red sole on footwear.”

[3] See, Christian Louboutin SAS v. Ashish Bansal & Anr. CS (COMM) 503/2016, Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018 and Christian Louboutin SAS v. Pawan Kumar & Ors. CS(COMM) 714/2016.

[4] Société Des Produits Nestlé S.A. v. Cadbury UK Ltd [2012] EWHC 2637.

[5] See, Brief for Tiffany (NJ) LLC and Tiffany and Company as Amici Curiae, Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America, Inc et al., No 11-cv-3303, (2d. Cir. Oct. 2011), ECF. No. 63.

[6] Lanham (Trademark) Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051-1141n (2012).

[7] See, Reanna L. Kuitse, “Christian Louboutin’s “Red Sole Mark” Saved To Remain Louboutin’s Footmark In High Fashion, For Now . . .” (2013) 46 Indiana Law Review 241.

See also, D.E. Gorman, “Protecting Single Colour Trademarks in Fashion After Louboutin”, (2012) 30 Cardozo Arts and Ent. L.J 122.

[8] See, Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[9] The Trademarks Act, (1999).

[10] Manual of Trademarks Practice and Procedure, 2015.

[11] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (1994). Available at: http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf (last visited on July 26th, 2012).

[12] Christian Louboutin SAS v. Van Haren Schoenen BV, Case C‑163/16 12th June 2018.

[13] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[14] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 778 F.Supp.2d 447 (2011).

[15] Louboutin, 696 F. 3d 220 (2d Cir. 2012).

[16] New Colt Holding Corp. v. RJG Holdings of Fla., Inc., 312 F. Supp. 2d 195, 212 (D. Conn. 2004).

[17]Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 778 F.Supp.2d 451 (2011).

[18] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[19] Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018.

[20] Louboutin, 696 F. 3d 238 (2d Cir. 2012).

[21] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[22] Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018.

[23] In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

[24] The Trademarks Act, (1999) § 2(zb).

[25] Brief for International Trademark Association (INTA) as Amici Curiae, at p.10, Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America, Inc et al., No. 11-cv-3303 (2d. Cir. Nov. 2011), ECF. No. 82.

[26] Christian Louboutin SAS v. Ashish Bansal & Anr. CS (COMM) 503/2016.

-

Poems3 years ago

Poems3 years agoPoems

-

Uncategorized2 years ago

Uncategorized2 years agoOnline Elocution Contest

-

Poems2 years ago

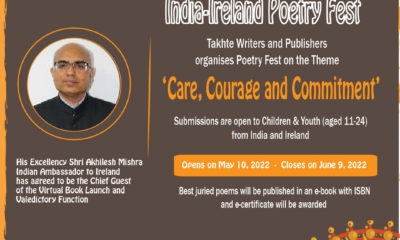

Poems2 years agoIndia-Ireland Poetry Fest

-

Legal Talks3 years ago

Legal Talks3 years agoCompliances Relating to the Commercialization of Electronic Devices

-

Legal Talks3 years ago

Legal Talks3 years agoCUSTODIAL RAPE IN LIGHT OF THE MATHURA GANG RAPE CASE

-

Art & Culture3 years ago

Art & Culture3 years agoThe Lore of the Days of Yore: Significance of History

-

Short-story3 years ago

Short-story3 years agoBibek’s visit at his friend’s bungalow

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Uncategorized1 year agoPotential Navigators of Knowledge (PNK) Young Authors Awards