Legal Talks

Biting the Cookie: Informed Consent and The Right to Privacy

Mahathi U

The National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi, Kerala

The methods of production, collection, combination, sharing, storage, and analysis of data on the internet are rapidly reorienting and thereby redefining personal data and the protection that ought to be given to it. Owing to this constant change, online privacy remains a predicament to consumers, policymakers, and web organizations.

When a website reads, “We use cookies to give you the best online experience,” this message is either ignored or accepted by the user. In doing so, little does the user know about these tiny text files that can be used to intrude into his privacy and access his data. Neither the Data Protection Bill nor the IT Act contains provisions to regulate cookies. A few provisions are so broad that cookies might fall under their ambit. But such legislative gaps only serve to weaken the privacy of people using the internet. This article attempts to propose a stipulation in Indian law to monitor and control the use of cookies on the world wide web.

That’s How the Cookie Crumbles:

The archetypal method of locating and tracking user activity online entails placing small text files or “cookies” on a user’s hard drive, which are given back to that website during successive visits by the user. They may be designed to stay on the hard drive for only the online session, which is currently in progress; they can be fashioned to last for any period or be designed to last eternally.

Undeniably, a few websites need cookies to operate effectively. E-commerce hubs form a part of this category, requiring the placement of cookies in the shopper’s drive in order to discern that shopper as the person who stored his items in his virtual shopping cart (Chapman and Dhillon 2002). However, cookies can make up an invasion of privacy from various standpoints: viz, their capacity to track users’ online behaviour; their clandestineness; their pervasiveness and duration; users’ lack of knowledge regarding the degree of threat they pose, their control and usage and their use by third parties.

The rise in software potentiality that augments user knowledge of efforts to place cookies indicates that greater consilience between disclosure and practice could be favourable to website organisations. Though a priori disclosure of cookies’ usage might lessen the negative effects of cookie detection of the user’s behavioural intentions, concerns about the ‘current process of disclosure’ are extant.

The rampancy of non – consensual identification has increased with the use of third-party cookies and original domain. These issues remain unaddressed and under-regulated by the Indian system.

So, the Indian regime must learn from the EU’s ‘Cookie law’. The EU’s cookie law is essentially a cookie consent directive that protects personal data privacy in the EU. This directive was intended to be the user’s defense against data profiling, tracking user behaviour, the harvesting of personal data without consent, and unwelcome marketing tactics through unsolicited advertisements and other notices.

As per a New York Times report, Europe is now the leading tech watchdog in the world, which is undoubtedly due to the existing cookie law and the broader GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the new ePrivacy Regulation will also strengthen it.

The pop-up windows and cookie consent notices that the user encounters as he surfs the web are attestations to the fundamental right to privacy under European law. Nevertheless, there are flaws in this regime, too, from which the Indian system needs to learn and improvise.

The ePrivacy directive clearly states that trackers and cookies must not be placed before getting the user’s consent, regardless of whether they contain personal data or not, except for those cookies which are strictly necessary for the basic functioning of that website. Despite this, many of the notices and pop-ups merely state that their website “uses cookies to enhance the user experience,” leaving the users with the only option to double-click on the “OK”, to signify their permission to access their personal data.

This results in a condition which is known as ‘consent fatigue.’ The user, in this situation, has no real choice of consent whenever he visits a website. Due to the lacuna, that user’s data continues to be harvested and marketed in the space below the internet visible to the naked eye, which makes up the most of that trillion-dollar economy.

The Indian regime, by not regulating the use of cookies or equivalently efficacious technology, directly enfeebles the right to privacy granted to every person; and every user of the internet, in the instant case. Under the IT Act, Section 43 restricts the access, download, copy, or extraction of any data, computer database, or information from any computer, computer system, or computer network without the owner’s permission or the person in charge. Though this provision may, at large, be taken to include the regulation of cookies, the users’ right to be notified of the presence of cookies in a particular webspace and his right to ‘do-not-track me’ options have not been included.

Privacy as a fundamental right is entrenched in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Data Protection Bill, recommended by the B. N. Srikrishna Committee, does not incorporate this imperative provision to protect said right either. However, it does contain provisions for informed consent with an exhaustive list of requirements to be fulfilled for the consent to be considered informed.

The suggestion made would be to append a provision which protects the personal data of the user, encompassing the facets of informed consent, the due process to be followed to obtain consent, and the rights and duties of a reasonable and responsible user of the internet, assuring the protection of his personal data.

The cookies lurking in users’ hard drive are nibbling away at their privacy and continue to leave a bad after-taste in the mouths of some, so dismiss the role of cookies at your own peril.

The methods of production, collection, combination, sharing, storage, and analysis of data on the internet are rapidly reorienting and thereby redefining personal data and the protection that ought to be given to it. Owing to this constant change, online privacy remains a predicament to consumers, policymakers, and web organizations.

When a website reads, “We use cookies to give you the best online experience,” this message is either ignored or accepted by the user. In doing so, little does the user know about these tiny text files that can be used to intrude into his privacy and access his data. Neither the Data Protection Bill nor the IT Act contains provisions to regulate cookies. A few provisions are so broad that cookies might fall under their ambit. But such legislative gaps only serve to weaken the privacy of people using the internet. This article attempts to propose a stipulation in Indian law to monitor and control the use of cookies on the world wide web.

That’s How the Cookie Crumbles:

The archetypal method of locating and tracking user activity online entails placing small text files or “cookies” on a user’s hard drive, which are given back to that website during successive visits by the user. They may be designed to stay on the hard drive for only the online session, which is currently in progress; they can be fashioned to last for any period or be designed to last eternally.

Undeniably, a few websites need cookies to operate effectively. E-commerce hubs form a part of this category, requiring the placement of cookies in the shopper’s drive in order to discern that shopper as the person who stored his items in his virtual shopping cart (Chapman and Dhillon 2002). However, cookies can make up an invasion of privacy from various standpoints: viz, their capacity to track users’ online behaviour; their clandestineness; their pervasiveness and duration; users’ lack of knowledge regarding the degree of threat they pose, their control and usage and their use by third parties.

The rise in software potentiality that augments user knowledge of efforts to place cookies indicates that greater consilience between disclosure and practice could be favourable to website organisations. Though a priori disclosure of cookies’ usage might lessen the negative effects of cookie detection of the user’s behavioural intentions, concerns about the ‘current process of disclosure’ are extant.

The rampancy of non – consensual identification has increased with the use of third-party cookies and original domain. These issues remain unaddressed and under-regulated by the Indian system.

So, the Indian regime must learn from the EU’s ‘Cookie law’. The EU’s cookie law is essentially a cookie consent directive that protects personal data privacy in the EU. This directive was intended to be the user’s defense against data profiling, tracking user behaviour, the harvesting of personal data without consent, and unwelcome marketing tactics through unsolicited advertisements and other notices.

As per a New York Times report, Europe is now the leading tech watchdog in the world, which is undoubtedly due to the existing cookie law and the broader GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the new ePrivacy Regulation will also strengthen it.

The pop-up windows and cookie consent notices that the user encounters as he surfs the web are attestations to the fundamental right to privacy under European law. Nevertheless, there are flaws in this regime, too, from which the Indian system needs to learn and improvise.

The ePrivacy directive clearly states that trackers and cookies must not be placed before getting the user’s consent, regardless of whether they contain personal data or not, except for those cookies which are strictly necessary for the basic functioning of that website. Despite this, many of the notices and pop-ups merely state that their website “uses cookies to enhance the user experience,” leaving the users with the only option to double-click on the “OK”, to signify their permission to access their personal data.

This results in a condition which is known as ‘consent fatigue.’ The user, in this situation, has no real choice of consent whenever he visits a website. Due to the lacuna, that user’s data continues to be harvested and marketed in the space below the internet visible to the naked eye, which makes up the most of that trillion-dollar economy.

The Indian regime, by not regulating the use of cookies or equivalently efficacious technology, directly enfeebles the right to privacy granted to every person; and every user of the internet, in the instant case. Under the IT Act, Section 43 restricts the access, download, copy, or extraction of any data, computer database, or information from any computer, computer system, or computer network without the owner’s permission or the person in charge. Though this provision may, at large, be taken to include the regulation of cookies, the users’ right to be notified of the presence of cookies in a particular webspace and his right to ‘do-not-track me’ options have not been included.

Privacy as a fundamental right is entrenched in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The Data Protection Bill, recommended by the B. N. Srikrishna Committee, does not incorporate this imperative provision to protect said right either. However, it does contain provisions for informed consent with an exhaustive list of requirements to be fulfilled for the consent to be considered informed.

The suggestion made would be to append a provision which protects the personal data of the user, encompassing the facets of informed consent, the due process to be followed to obtain consent, and the rights and duties of a reasonable and responsible user of the internet, assuring the protection of his personal data.

The cookies lurking in users’ hard drive are nibbling away at their privacy and continue to leave a bad after-taste in the mouths of some, so dismiss the role of cookies at your own peril.

Legal Talks

CUSTODIAL RAPE IN LIGHT OF THE MATHURA GANG RAPE CASE

By Nishtha Kheria and Varun Vikas Srivastav

Amity Law School, Noida

Abstract:

In this article, we would like to look at the changes, which came after the monstrous incident took place, i.e. Mathura rape. In the past years, there have been many attempts to bring changes in the laws relating to rape, but the question remains the same has there been any change in the law? If we look at the Supreme Court’s judgments, it is evident that the same ideology is still used as it was in the Mathura rape case. The concepts related to the consent and the non-consent are still the vital issue because even the law changes have not able to address the passive consent. This article will cover why even the modifications bought in law has not been able to bring the changes in the rates of conviction. This is related to law and regards the cases that are not related to rape and is significantly based on sympathy and intentions. By the end of the article, it would be clear that the law is changing every day, but there is a need to mold it so that women’s development takes place as a subject to the law and not as an object.

Keywords: Changes, Judgments, Conviction, Consent, Sympathy.

Introduction

The whole women group had come together as one was when the Mathura rape case took place[i], on 26th of March 1972, the Mathura rape case which was related to the Custodial rape had taken place where two policemen raped a girl who belonged to the Harijan Community in the police station of Chandrapur district of Maharashtra after which the amendment named as the Criminal Law Amendment of 1983 had taken place in the rape laws.[ii]

Facts

In this case, a girl whose name was Mathura who used to work as a labourer in the house for employment. While she was working there, she had developed sexual relations with the son of the place she worked with whose name was Ashok. After which Ashok and Mathura decided to get married. Mathura’s brother had filed an FIR in the police station stating that Ashok had kidnapped her on 26th March 1972. After which, the police took Ashok and Mathura’s statements and asked all other constables to leave[iii].

After the incident had taken place, Mathura was correctly examined by the doctors, and it was said that there was no injury on her body. There were no pubic hair, or semen found instead strays of semen were found on her clothes. The estimated age of Mathura was around 14 to 16 years. [iv]

Issues

The various issues in this case were:

- Had Mathura consented for sexual intercourse?

- Will the accused get charged with section 376 of the Indian penal code?

- Will the acts of the police officers be addressed as rape?

- The decision of the court of acquitting the accused validly?

Arguments

This case argued that the session court had said that the intercourse had taken place with consent because she wanted to fulfil her sexual desires. After which the high court had reversed the trial court’s decision and had held that the sexual intercourse has not consented and was rape. Later, as per the shreds of evidence presented to the supreme court, it was said that Mathura was habitual of sexual intercourse. Both the accused were acquitted and were not charged with Section 376 of the Indian penal code.

The Analysis of Section 376 of IPC

In cases which are provided in Sub-Section (2) then they will be punished with an imprisonment of a term which is not less than seven years or which can extend to ten years and will even have to pay fine until he has not raped his wife or is under the age of twelve years then he will be punished for about imprisonment of two years or with fine or both if the court has a specific reason then they can be imprisoned for less than seven years.

The analysis before the amendment of criminal law 2013

Rape laws have changed a lot of time before attaining the present condition of the criminal law amendment 2013. This amendment took place after the rape case of a physiotherapist in Delhi. Nirbhaya case shook the nation – March 2014. Judiciary spurred into action and laws were strengthened for sex offenders. Four out of the five accused in the horrific gang-rape case of Nirbhaya were convicted and given the death sentence.

The case also resulted in the introduction of the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013 which provides for the amendment of the definition of rape under the Indian Penal Code, 1860; Code of Criminal Procedures, 1973; the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012.

Rape is defined under Section 375 of the Indian penal code. Rape refers to the act where sexual intercourse takes place with a woman without taking permission and doing through force or fear. Due to Tukaram vs state of Maharashtra (Mathura rape case) the amendment of 1983 was brought.

Due to this case, the amendments had taken place in the evidence act and the Indian penal code. In the Indian penal code, section 376 A to D was added, and in evidence act section 114A was added. Before the amendment of 2013 took place, rape was referred to as the non-consensual sexual intercourse between man and woman. [v]

Rape law after the amendment of criminal law 2013

The amendment of the criminal law 2013 has even provided an amendment in the Indian penal code, evidence act, and the code of criminal procedure related to the laws of sexual offences.

Due to the cases, there was a widespread protest in society because the lawmakers were forced to amend the rape laws. The sole purpose of the amendment was to make the punishments of rape stricter and not to broaden the definition of rape.

Due to the new amendment now the definition of rape includes the punishment for all the kinds of penetration in any part of a girl’s body. This even includes that according to the fifth law commission report, any penetration would consent would be referred to as rape. [vi]

In 2018 a Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance was introduced, which amended the Indian Penal Code 1860. The punishment provided for the rape of women was increased from seven years to ten years.

If rape or gang rape occurs on girls below the age of 12, the perpetrators will suffer a punishment of minimum imprisonment of twenty years and can even get extended up to life imprisonment or the death penalty.

Rape or Gang rape of girls below 16 years of age will also suffer imprisonment of twenty years or life imprisonment. This new ordinance had increased the punishment for girls, but the punishment for rape of boys has still experienced no change.

The Key features of this ordinance are that it amends

Under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860,

- Acid Attack(Sections326A and 326B)

- Rape (Section375, 376, 376A, 376B, 376C, 376D and 376E)

- Attempt to commit rape (Section 376/511)

- Kidnapping and abduction for different purposes (Sections 363–373)

- Murder, Dowry death, Abetment of Suicide, etc. (Sections 302, 304B and 306)

- Cruelty by husband or his relatives (Section 498A)

- Outraging the modesty of women (Section 354)

- Sexual harassment (Section 354A)

- Assault on women with intent to disrobe a woman (Section 354B)

- Voyeurism (Section 354C)

- Stalking (Section 354D)

- Importation of girls up to 21 years of age (Section 366B)

- Word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman (Section 509).

Special provisions to protect women and their interests-

- The Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956

- The Dowry (Prohibition) Act, 1961

- The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929

- The Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986

- The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987

- Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013.

POCSO Act, 2012, and other laws related to the rape of women. The POCSO, Act states that the higher punishment between the POCSO Act and the IPC will apply to minors’ rape.

Reasons for enactment

The criminal law amendment bill 2013 was formed because of the brutal gang rape and the death of the physiotherapist in Delhi led to the amendment of the laws related to sexual offences in the country. This new act has mainly amended the Indian penal code, code of criminal procedure, and Indian evidence act.

In a case in 2016, there was a case pertains to an allegation of rape by a woman in Bangalore 19 years ago. While the Sessions Court had acquitted the three men accused, the Karnataka high court later sentenced them to life imprisonment. The Supreme Court has set aside the high court judgment and set free the accused, citing reasons including inconsistencies in the woman’s statements, hostile witnesses, and the medical report conducted after the incident.

Judgment was given by the session court

The session court had said that the girl was habitual of sexual intercourse and the intercourse between the accused and the girl was done by consent; therefore, both the accused are not liable for the offense.

Judgment was given by the high court

The judgment given by the session court was then reversed by the high court of Bombay stating that the sexual intercourse taken place was not by consent instead, it was rape. It was proved by evidence that the accused were unknown to Mathura then how can she have sexual intercourse with them through consent.

Judgment by the supreme court

The supreme court had again reversed the order of the high court and said that the sexual intercourse was a consented one and not rape thus agreeing with the session court decision.

Loopholes in the judgment

In the case of Mathura rape case, the various loopholes which should have been taken into consideration were:

- The acquittal was granted to the accused by the supreme court on the sole ground that the girl did not have any injuries; therefore it is not rape.

- It is not a valid reason that there was no alarm for help by the girl then it was consensual intercourse between the police and the girl.

- The greatest loophole was that the accused should have been provided harsher punishments as related to the criminal law amendment.

- The judiciary system should take proper steps in the case of the minors and the majors in such offenses.

Organizations in India helping women in cases of Molestation, Sexual Abuse, and Violence

In 2020 there are various organizations formed for the assisting of women and children during their distress and victims of the Molestation, Sexual Abuse, and Violence.

Some of these organizations and NGOs are

- National Commission for Women Guria India

- Women Helpline (All India)- Women in India

- The Pranjya Trust

- Action Aid India

- Snehalaya

- Majlis

- Azad Foundation

- International Center for Research on Women

- Aasra

- SNEHA

Conclusion

In the case of the Mathura gang rape case, the victims were acquitted by the appellate courts. If we compare both the legislations of both before 2013 and after 2013 then there is a drastic change in the laws related to rape. The Mathura rape case was a case that had received a lot of criticism after the independence and because of which the amendment took place in the criminal law. Then finally after the Delhi gang-rape case in 2013, the laws related to rape have not only changed but the definition of rape has changed and has widened its scope.

[i]B. Suguna (1 January 2009). Women S Movements. Discovery Publishing House. pp. 66–. ISBN 978-81-8356-425-0. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

[ii]Basu, Moni (8 November 2013). “The Girl Whose Rape Changed A Country”. CNN. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

[iii]Maya Majumdar (1 January 2005). Encyclopaedia of Gender Equality Through Women Empowerment. Sarup & Sons. pp. 297–. ISBN 978-81-7625-548-6. Retrieved 9 June 2013

[iv]Kamini Jaiswal (12 October 2008). “Mathura rape case”. The Sunday Indian. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

[v]”Rape law, a double-edged sword in India”. CNN-IBN. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

[vi]Sarah Gamble (ed.) (2001). The Routledge Companion to Feminism and Post feminism. Routledge. ISBN 0415243106.

Legal Talks

Tread Lightly: Single Colour and Trademarks

Mahathi U

The National University of Advanced Legal Studies, Kochi, Kerala

That brand behemoths have systematically swallowed up every square footage of high streets is hardly news. Exuberant hues are used judiciously by these brands to draw the consumer towards the product. When such a product sells, fashion brands seek protection from the law for many aspects of clothing and accessory designs, including colours, which can serve as source-identifiers or marks and Trademark law is generally the primary protection sought by fashion brands and designers alike.

This article, for the most part analyses the existing jurisprudence on the single colour mark and the rest emphasizes the need for Indian law to recognize a single colour as a mark, with specific reference to the Louboutin cases.

Fetching sky-high prices and featuring sky-high heels, Louboutin’s red-soled stilettos, are considered to be an utterly iconic symbol of femininity. These fiery red outsoles, have been the subject of many litigations. The first one is Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America[1], with Louboutin suing for trademark protection of his red lacquered sole. In India, the case for red soles[2] has shaken up the judiciary. The High Court of Delhi appears to have slid into a quagmire of sorts because of the three Louboutin cases[3], and the status of the single colour trademark remains uncertain.

Single Colour Mark Jurisprudence:

Drawing a connection between a colour and a brand story, requires more than just ink, pixels, and a lawyer. In Cadbury’s case, the value of owning the colour ‘purple’ would be attached only when it symbolizes a broader brand experience that can delight consumers everywhere.[4] Tiffany’s on the other hand, has been using the sought-after ‘robin blue’ since 1845, but trademarked it only in 1998, all the while managing to retain its brand equity.[5] Both these establishments, in an effort to exclude other brands from deriving any benefit accrued from their unique mark, have sought protection from trademark law.

Under U.S. Trademark Law, the protection awarded to single colours does not extend to colours per se, implying that protection is afforded only to the coloration of a specific product, shape or design.[6] The Pantone Matching System is utilised by the American Judiciary in order to define the scope of trademark protection of a colour so that there exists a standard, objective benchmark that ought to be complied with.[7] The logic behind the confines is that if a colour yields a utilitarian advantage, protecting it as a trademark would unjustly restrict competitors’ ability to compete in the industry.[8]

Contrarily, the Trademarks Act[9] in India does not expressly provide for the protection of single colour trademarks. But the practice guidelines[10] that are drafted by the Trade Mark Office suggest that single colours will be protected on strict evidence of “acquired distinctiveness” and that registration of a single colour will be allowed only to the extent of the colour shade.

This issue had also come up for consideration at the European Court of Justice, which disregarded the recommendation of the Advocate-General and declared the accepted position under European Trademark Law. The provisions of TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) were analysed and applied to the case at hand.[11] It stated that seeking to protect the application of a colour to a specific part of the shoe was admissible. [12]

The single colour mark regime has, ergo, been subjected to interpretation by various legal systems and their views remain divided.

The Rule of Aesthetic Functionality and the Flawed Colour Depletion Theory:

The Court of Appeal in Christian Louboutin SA v. Yves Saint Laurent America[13], addressed the doctrine of “aesthetic functionality” as considered by the District Court[14]. The Hon’ble Court also decided on whether the single colour mark was necessarily ‘functional’.[15] The “functionality” of a mark is demonstrated by, inter alia, showing that the mark has a traditional or aesthetic functionality.[16] The common denominator in cases where the functionality doctrine is applied, is whether the element in question has helped in the commercial success of the product.

In order to justify the employment of this rule, the District Court stated that “there is something unique about the fashion world that militates against extending trademark protection to a single colour.”[17] It was in this landscape that the suit was decided against Louboutin. This rationale, however, is faulty for the following reasons.

Firstly, the argument is very general, vague, and the phrase ‘something unique’ has not been elaborated upon. Secondly, the defense of functionality does not guarantee an inordinate range for a competitor’s creative outlet, but only the wherewithal to fairly compete within a given market. Competition considerations must not in any manner outweigh intellectual property rights; they must only step in when necessary.

The Court of Appeal clarified its stance on this issue, denouncing the decision of the District Court. It held that “the District Court’s conclusion that a single colour can never serve as a trademark in the fashion industry was based on an incorrect understanding of the doctrine of ‘aesthetic functionality’ and was therefore error”.[18]

The High Court of Delhi too, in the 2nd Louboutin case[19], seems to have erred in its interpretation of this rule. It has cited the U.S. Court of Appeal as having “categorically observed that where a trademark serves a significant function or the trademark is such that there is a competitive need for the colours to remain available in the industry”, then there remains special reasons which oppose the use of colour alone as a trademark.[20] It has clearly backed the wrong horse by attaching functionality to colour in the case at hand.

The competition versus trademark protection problem in the market is further convoluted by the argument of limited availability of colours, or as it is referred to in the United States, the colour depletion theory.[21]

This theory forms the basis for the Hon’ble Court’s ground for dismissing Louboutin’s plea[22] to recognize his red-sole as a mark, is one that bars the use of colour as a trademark. Its premise which is quite flawed, is that the number of colours in the visible spectrum is finite and therefore, limited. It suggests that if a manufacturer is allowed to appropriate a colour for its goods, and in doing so, is followed by others, at a later point in time, manufacturers will have little to no colours for future utilization.

In the Owens-Corning case, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that, based on a broad revision of trademark law, “courts have declined to perpetuate the colour depletion theory’s prohibition” on infringement protection. [23] This theory has to be rejected because it relies on an infrequent problem in order to legitimize a blanket prohibition.

The Trademark Act, 1999 only allows for a combination of colours to be agnized as a mark under Section 2 (zb)[24]. The object of this provision is to enable the Indian system to prevent the exhaustion of colours. But, in not appending a ‘single colour’ to the section which defines mark, the legislature is denying the right that every brand has, to protect its distinctive identity. This theory effectively denies protection of a colour even after it has achieved secondary meaning resulting in the mischaracterization of the mark as being of monopolising nature.[25]

As amply substantiated above, the rule of aesthetic functionality and the colour depletion theory stand inapplicable in this case, as is.

The Indian Position: What is to be done?

The single colour trademark, forms a grey area in Indian Trademark Law. It purportedly lacks distinctiveness which a combination of colours has. Such an argument is liable to be qualified as unsound and fallacious for reasons which are explained in the following paragraphs.

The latest judgment[26] in the Delhi High Court was decided in Louboutin’s favour. Nevertheless, the judiciary’s only reasoning was that this trademark is protected everywhere and that it has the requisite distinctiveness.

The distorted rationalization in the analysis of the regime is this. Both the Legislature and the Judiciary have developed a misconstrued notion that there might befall a situation where trademarks are to be awarded to colours per se but that is never the case and never will be. The per se rule would essentially deny trademark protection to any application of a single colour on an apparel. Even if the Judiciary wanted to read the per se rule of functionality into this issue, such a rule would be neither appropriate nor necessary here, because this single colour which has been the object of continuous deliberation, will inevitably have to be deployed on a particular product, or serve as an identifier for a specific shape or design. So, undeniably, it cannot be a trademark by and of itself. The secondary meaning or the plus factor is already inherent in the case of a single colour.

Moreover, competition in this billion-dollar industry is not possible without the protection of intellectual property in general and the single colour mark in the instant case. A definitive and acceptable system of protection inspires traders to flesh out new brands and play an active role in business development, thereby helping to maintain a fair competitive market.

The legislation therefore, has to be revamped in such a manner that the definition for mark is inclusive of a single colour. For fear of exhaustion of single colours from the ostensibly limited palette, the judiciary may be satiated by utilising the ‘functionality’ doctrine in the appropriate circumstances, thereby successfully aiding the legislature in preventing unfair competition in the free market.

By extending trademark protection to the coloration of an item of apparel, there is a justified competitive advantage given to a trader. This in turn will serve as a brand-identifier and, brand identity, is a proven neurological mnemonic that influences our thought process. So, dismiss the role of a single colour at your peril.

[1] Christian Louboutin S.A. v Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[2] Specifically, the registration for the Louboutin mark states: “The colour red is claimed as a feature of the mark. The mark consists of a lacquered red sole on footwear.”

[3] See, Christian Louboutin SAS v. Ashish Bansal & Anr. CS (COMM) 503/2016, Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018 and Christian Louboutin SAS v. Pawan Kumar & Ors. CS(COMM) 714/2016.

[4] Société Des Produits Nestlé S.A. v. Cadbury UK Ltd [2012] EWHC 2637.

[5] See, Brief for Tiffany (NJ) LLC and Tiffany and Company as Amici Curiae, Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America, Inc et al., No 11-cv-3303, (2d. Cir. Oct. 2011), ECF. No. 63.

[6] Lanham (Trademark) Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051-1141n (2012).

[7] See, Reanna L. Kuitse, “Christian Louboutin’s “Red Sole Mark” Saved To Remain Louboutin’s Footmark In High Fashion, For Now . . .” (2013) 46 Indiana Law Review 241.

See also, D.E. Gorman, “Protecting Single Colour Trademarks in Fashion After Louboutin”, (2012) 30 Cardozo Arts and Ent. L.J 122.

[8] See, Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[9] The Trademarks Act, (1999).

[10] Manual of Trademarks Practice and Procedure, 2015.

[11] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (1994). Available at: http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf (last visited on July 26th, 2012).

[12] Christian Louboutin SAS v. Van Haren Schoenen BV, Case C‑163/16 12th June 2018.

[13] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[14] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 778 F.Supp.2d 447 (2011).

[15] Louboutin, 696 F. 3d 220 (2d Cir. 2012).

[16] New Colt Holding Corp. v. RJG Holdings of Fla., Inc., 312 F. Supp. 2d 195, 212 (D. Conn. 2004).

[17]Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 778 F.Supp.2d 451 (2011).

[18] Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent Am., Inc., 696 F. 3d 206 (2d Cir. 2012).

[19] Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018.

[20] Louboutin, 696 F. 3d 238 (2d Cir. 2012).

[21] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

[22] Christian Louboutin SAS v Abubaker CS (COMM) No 890/2018.

[23] In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

[24] The Trademarks Act, (1999) § 2(zb).

[25] Brief for International Trademark Association (INTA) as Amici Curiae, at p.10, Christian Louboutin SA v Yves Saint Laurent America, Inc et al., No. 11-cv-3303 (2d. Cir. Nov. 2011), ECF. No. 82.

[26] Christian Louboutin SAS v. Ashish Bansal & Anr. CS (COMM) 503/2016.

Legal Talks

Privacy Laws & Consent while using Image of Random People Clicked on Street for Facial Recognition

Varun Vikas Srivastav

Amity Law School, Amity University, Noida, Uttar Pradesh

Privacy laws are the kind of laws that do not fall within the rubric of Intellectual Property laws. There are situations where they both come up in the same situation. For instance, in the areas of laws where different jurisdictions address the lawful ideas differently. Personality rights are considered to be the umbrella term for the rights of publicity and privacy[1]. In some situations, the Right of publicity is known to operate similarly as a trademark i.e. It is the right to keep one’s image from being exploited commercially without taking any permission or compensation from an agreement[2]. If we talk about privacy rights, then it is known to be a huge and debated field of law and can sometimes be referred to as the right to be left alone, but generally, they operate non-commercially[3].

Facial Recognition Programs a Threat to Privacy:

Facial recognition refers to when the face mapping techniques are used to identify the individuals’ facial features and then compare them with the available databanks. This Technology is widely prevalent in both the private and the public sectors used by the governments of various countries for the surveillance and enforcement of the law[4].

In India, when the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 was passed there was a large amount of protest taking place across India. At that time the facial recognition technology was used in the streets amidst the protest so that the protestors could be identified easily and could be arrested. These facial recognition systems are even widely used in Indian airports[5]. This technology will even facilitate the identification of the criminals, the unidentified dead bodies, and even help in finding the children who have gone missing. Thus, it will not violate the rights of the citizens[6].

The various human right activist of India is opposing the use of these technologies because these are violating the right to privacy which is being guaranteed by the constitution of India under Article 21.[7]

The legal challenges faced by facial recognition technology:

In the Case of Justice KS Puttaswamy vs, the Union of India[8] the supreme court of India had held that the right to privacy is guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian constitution. It even stated that it is necessary to take the consent of the person before collecting the data[9].

In India, there are no data protection laws framed so far which can define the scope of this technology. But this technology is still utilized blatantly by the Indian government for the collection of private data through the process of multiple state surveillance on the streets. This practice of the Indian government is violating various domestic and international laws. The laws violated are article 17 of the international covenant for civil and political rights and article 12 of the universal declaration of human rights[10].

The Automated Facial Recognition Systems (AFRS) are implemented on the streets which are in turn aggravating the privacy norms as these technologies are not taking consent from the people. The facial recognition software only works if there is a database of the images and videos existing so that the algorithms can identify and detect the faces of people.

There are reports which clearly express that the facial recognition tools use a plethora of images which are taken by the internet without taking any consent from the person. Thus, we can say that there is a violation of the law[11].

The Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 and its Impact:

In 2019, the Government of India had introduced the Personal Data Protection Bill. The Automated Facial Recognition Systems (AFRS) were also made legal by the lower house of the parliament[12].

This New Bill provided the Government with Three Exceptions which are as follows:

- It granted the government the right to collect private data without even taking consent from the concerned person when there is a matter relating to the security of the state and the public order.

- The government can collect the data of the person so that they can detect or prevent any offense.

- The government can collect data for any other reasonable purpose.

This bill formed did not contain the provision of taking consent therefore this bill was considered to be a complete failure. A presumption was made that any other law-making body will be handling this, but this also didn’t take place[13].

The Situations which are provided with the exemption from the Application of the Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 are:

- Specific situations: These are the situations which are provided with the cover on the core provisions of the bill which in turn facilitating in imposing of the obligations on the data fiduciaries and makes it necessary to take consent, ensure the rights of people, transparency and lastly they provide with the protection to the personal data of the people from getting transferred to outside India.

- Blanket exemption: This is an exemption which the central government has the right to apply at their own will. Through this, the central government receives the right to facilitate the removal of any or all of the protection granted by the data laws, by a government agency, or any of the personal data that the central government will decide by its discretion.

In some instances where the protestors can be seen as threatening to commit any act or crime which is punishable by law then their data recording and collection can be exempted from the procedural requirements of the data protection law.[14]According to the reports, the Delhi police have started to use the automated facial recognition software on the streets of the protest venue.[15]

In countries such as the Hongkong and the United States, people have recognized the threat of technology surveillance in the protests because of which they have started to use face masks to avoid the collection of any face recognition data because of which the government had to ban the use of the masks. But these acts of mask banning were challenged in court and have proved to be unconstitutional. Such acts can soon take place in India too.

The PDP bills have prohibited the use of any kind of sensitive personal data such as biometric data by the use of new technologies and have not taken any data protection impact assessment.

Does the PDP Bill facilitate the Sharing or Drone recorded Information for Propaganda?

In India, the drones are used after full permission and compliance with the domestic regulations, but still, there can be various instances of Data privacy.

The Hungarian data protection authority has stated about using drones to have data protection implications. It there is a proper use of drones then it can prove to be invasive in the privacy of the people because the drones can collect every data which falls within the vision and is unusually wide.[16]

The data collected through drones installed with the cameras will collect and monitor the personal data of the people and fall within the ambit of the PDP bill 2019 because the person will be directly recorded through the footage.

The recording done by the drone can be easily used as a facial recognition software and can even contain the biometric data within them. Such information can further reveal the religious beliefs, sexual orientations, caste, tribe, transgender status, etc. These are considered to be private data and should be protected under PDP bill.

Therefore, we can say that the drones which are used for the collection of the footage of people without their consent can be considered impermissible by the bill. If still the information is collected through the drones, the person will be liable for up to INR 15 crore under the Bill.

The requirement of the efficient laws in India for the protection of the biometric data:

In India, there are no safeguards formed and the government of India has formed a regime that has provided with permission to surveil its citizens. The government of India has even provided with the permissions to the airports to use face recognition for the normal boarding passes.

In Countries such as San Francisco[17], California, etc. Have prohibited the use of facial recognition software’s because this technology is violating the rights of privacy granted to the citizens. The issues of privacy are even arising in India but the government of India is not taking proper steps and there is a need to introduce the data protection laws.[18] There is a need to obtain proper express as well as affirmative consent with the existing FTC standards which are in practice. No unique biometric identifier can be created and even maintained over time if proper consent is not taken for the same.

Through this paper, it is clear and can be concluded that if the government is planning to make use of the facial recognition software then the government should also introduce some proper safeguards and should even form the redressal mechanisms so that the people whose rights are violated through these acts can gain speedy disposal of their cases. Each Indian citizen has the right that they should be handled with proper care before they are subjected to the flawed technology which does not even have the safeguards. Until the safeguards are formed the government should withdraw all the policies that violate the rights of the people and pry into their lives. The government should pass laws that mainly focus on privacy laws.

The PDP Bill is prohibiting the recording of the footages of the people which is done without even taking permission from the people who are being filmed and are Imposing strict penalties on the people who are doing this act without taking prior permission. But if the recording is done with the proper direction of the tribunals and the courts then the PDP bill provides with the exception from gaining consent from the concerned person.

[1] Navaneeth Kamballur Kottayil,”What is Facial Recognition? – Definition from Techopedia”. Techopedia.com. (Last accessed 2018-08-27)., available at https://www.techopedia.com/definition/32071/facial-recognition.

[2] Andrew Heinzman. “How Does Facial Recognition Work?”. How-To Geek. (Last accessed 2020-02-28), available at https://www.howtogeek.com/427897/how-does-facial-recognition-work/.

[3] Steve Symanovich ,”How does facial recognition work?”. us.norton.com, (Last accessed 2020-02-28). available at https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-iot-how-facial-recognition-software-works.html

[4] “Face Recognition Applications”. Animetrics. Archived from the original, (Last accessed 2008-06-04), available at https://web.archive.org/web/20080713020541/http:/www.animetrics.com/Technology/FRapplications.html

[5] Consumer Report, “Facial Recognition: Who’s Tracking You in Public?”. Consumer Reports. (Last accessed 2016-04-05). Available at https://www.consumerreports.org/privacy/facial-recognition-who-is-tracking-you-in-public1/

[6] Bramer, Max, Artificial Intelligence in Theory and Practice: IFIP 19th World Computer Congress, p. 395

TC 12: IFIP AI 2006 Stream, Santiago, Chile. Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media. August 21-24, 2006,

[7] De Leeuw, Karl; Bergstra, The History of Information Security: A Comprehensive Handbook. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 264–265 Jan (2007).

[8] KS Puttaswamy vs, the Union of India, (2017) 10 SCC 1

[9] R. Brunelli, Template Matching Techniques in Computer Vision: Theory and Practice, Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-51706-2, 2009 ([1] TM book)

[10] Duhn, S. von; Ko, M. J.; Yin, L.; Hung, T.; Wei, X. “Three-View Surveillance Video Based Face Modeling for Recognition”, pp. 1–6, ISBN 978-1-4244-1548-9. (Last accessed 1 September 2007).

[11] Socolinsky, Diego A.; Selinger, Andrea “Thermal Face Recognition in an Operational Scenario”. IEEE Computer Society. pp. 1012–1019 – via ACM Digital Library. (1 January 2004). Available at https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/1896300.1896448

[12] Ministry of Law & Justice, “The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019”. PRS India. (11 December 2019), available at https://www.prsindia.org/billtrack/personal-data-protection-bill-2019

[13] SriKrishna Committee, “Key Changes in the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 from the Srikrishna Committee Draft”. SFLC.in. (Last Accessed 21 December 2019) Available at https://sflc.in/key-changes-personal-data-protection-bill-2019-srikrishna-committee-draft

[14] Shruti Dhapola, “Personal Data Protection Bill 2018 draft submitted by Justice Srikrishna Committee: Here is what it says”. The Indian Express. (Last Accessed 28 July 2018), available at https://indianexpress.com/article/technology/tech-news-technology/personal-data-protection-bill-2018-justice-srikrishna-data-protection-report-submitted-to-meity-5279972/

[15] “Personal Data Protection Bill 2018”. Meity Govt, (Last Accessed 11 December 2019), (India)

[16] Bhatia, Gautam “India’s Growing Surveillance State: New Technologies Threaten Freedoms in the World’s Largest Democracy”. Foreign Affairs. (Last accessed 21 February 2020), Available at https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2020-02-19/indias-growing-surveillance-state

[17] Gregory Barber, “San Francisco Bans Agency Use of Facial Recognition Tech”. Wired. ISSN 1059-1028 (Last accessed 14 May, 2019) available at https://www.wired.com/story/san-francisco-bans-use-facial-recognition-tech/

[18] Mandavia, Megha “Personal Data Protection Bill can turn India into ‘Orwellian State’: Justice BN Srikrishna”. The Economic Times. (Last Accessed 21 December 2019) Available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/personal-data-protection-bill-can-turn-india-into-orwellian-state-justice-bn-srikrishna/articleshow/72483355.cms

-

Uncategorized3 years ago

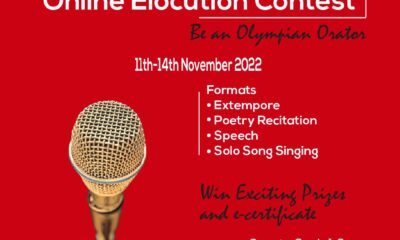

Uncategorized3 years agoOnline Elocution Contest

-

Legal Talks5 years ago

Legal Talks5 years agoCUSTODIAL RAPE IN LIGHT OF THE MATHURA GANG RAPE CASE

-

Poems5 years ago

Poems5 years agoPoems

-

Legal Talks5 years ago

Legal Talks5 years agoCompliances Relating to the Commercialization of Electronic Devices

-

Poems4 years ago

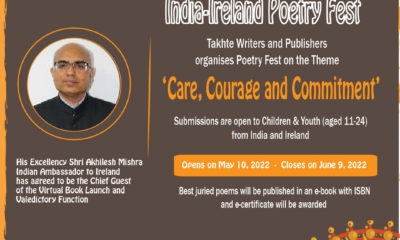

Poems4 years agoIndia-Ireland Poetry Fest

-

Art & Culture5 years ago

Art & Culture5 years agoThe Lore of the Days of Yore: Significance of History

-

Short-story5 years ago

Bibek’s visit at his friend’s bungalow

-

Legal Talks5 years ago

Legal Talks5 years agoPrivacy Laws & Consent while using Image of Random People Clicked on Street for Facial Recognition